Remembered and Retold - Life Story of the Otto Family

Chapter 1

Jürgen's Story

It must have been a lucky day for my mother, when she gave birth to her first son. She always told me: "You are a 'Sonntags Kind'. You will be very lucky in your life." Born in Sunday meant a good omen. Times were tough in the nineteen-twenties. My father had just started his practice in Berlin-Spandau. He had been a military surgeon ever since graduation from the University of Berlin in 1905 and now had to adjust to the fact that it was necessary to make a living as a general practitioner, something not very easy. Patients paid rather in goods than in money, super-inflation was cutting the value of the Mark in half every week, and if a patient paid in cash, my mother had to run to the store with the money and buy anything she could get hold of The next morning prices were already higher again.

Baby picture of Jürgen Otto

My father delivered me on the sofa in our apartment. Hospital deliveries at that time were not the normal way to have a baby. Since my parents had already a two-year old daughter I, a boy was accepted as a welcome addition to the family. It took me thirty-three years to find out that I had a lucky birth date. In Europe the day comes before the month. When I was in Las Vegas for the first time in 1953 I found out at the crap table that 7-11-20 is a lucky number which brought me my first and only winnings.

My parents did choose Spandau to settle down since it was at the fringes of Berlin and had still a touch of a country-side atmosphere. Our street corner was paved with very rough cobble stones at the Kirchhofstraße. Our apartment house with the number two was our playground. To ride with a bicycle over the rough pavement was almost impossible. My father had to struggle to get a good practice established and the habit of patients to pay their bill a week late during the inflation had often made the money worthless. The barter-system had taken over, and grocery goods and services took the form of payments. One day a patient paid my father with three sacks of flour. My mother, coming from a very thrifty family, could not get herself to throw even the empty flour sacks away. She washed and dyed the rough cloth and made dresses for me and my sister Gisela. She embroidered the dresses around the edges.

My mother told me repeatedly: "Hans Jürgen, you look very cute hi this dress, let's take a picture" - just to keep me from complaining about having to wear a girl's dress at the age of three. There still exists a picture of myself dressed in the homemade garment while I stand holding the chain of an old teddy bear, a gift from my grandmother.

Vitamins had not yet been discovered. Rickets took its toll in early childhood. Cod-liver oil was the only remedy for its prevention. Vague memory of that time clearly reminds me of the fight over and aversion to this fishy smelling liquid which I had to take each morning.

Antibiotics and immunizations, except for smallpox, had not entered the medical field. We all went through the childhood diseases like measles, scarlet fever, diphtheria and whooping cough. My parents must have had plenty of worries getting us through these diseases, almost unknown to today's parents.

My grandparents had settled in a picturesque little town on the Weser river. They were anxious to see their first male grandchild. An invitation arrived from my grandparents to present the first grandson to the older generation. My grandmother's parents had owned a drugstore in Berlin. Thanks to that solid financial background, she could afford and was given the permission to marry my grandfather, a young captain in the Kaiser's Army. The military pay for a captain was not enough to sustain a family. At the end of World War I my grandfather had left the military service with the rank of a general. They had bought a house with a huge garden in the city of Karlshafen. A several hundred-year-old oak tree shaded the house and the yard. It was so tall, one could see it from a mile away. Here the first recollection comes to mind.

Jürgen as a Student

It was a day in the fall of 1923. An emergency call from my grand-mother brought my parents to their home in Karlshafen. A tram ride with three changes of trains brought us to the railroad station on the Weser river. Grandfather was seriously ill. The three daughters had gathered around his bed in the bedroom of the two story house. A few rain drops on the window panes sparkled as they rolled down. The sun had found a spot to penetrate the heavy clouds and reach the sweat soaked face of my grandfather Gerhardy. They had him propped up in his pillows. His noisy gasping breath scared everybody in the room. This was the first time since our arrival in this medieval town in the heart of Germany that I, a 3 and 1/2 year old grandson, was allowed to enter the bedroom of my grandfather. It left an indelible imprint in my memory. I can still visualize the situation. Here begin my recollections for the first tune. The memory gives me even today the feeling, that I had entered the real world and could take part hi its happenings.

All his children including his wife were standing around the bedside. My mother was holding his hand, wiping his face and crying. Nobody had told me that grandpa was so sick and lying on his death bed. I only knew him from the life-sized oil painting hanging in his study. The bright colorful uniform of a general with his decorations looked awe-inspiring. His round head and steel blue eyes cast a penetrating look at the observer. His mustache shaped after the Kaiser's fashion, underlined his stern face' Later, when I saw in a history book the picture of the Minister President Graf von Bismarck, I recognized the similarity between m grandfather and Graf Bismarck. The atmosphere in the bedroom did not reflect any of the awe and sometimes fear with which he had dominated his family. In his home there were no embraces, no hugging, no kissing, but love and care was felt only in his actions and the security he gave his family. Open expressions of emotions did not surface. Grandfather Gustav Leopold Gerhardy - so I heard from my mother 20 years later - was a stern disciplinarian. Now the tears were running down the cheeks of everyone in the room. An illustrious life was coming to an end.

Early gangrene grandfather's of foot had led to blood poisoning with pneumonia, which at that time resulted in certain death. The family had hoped that my father, the-son-in-law physician, would help ease the last moments of his struggle for life. I watched my father as he took a glass-syringe out of a metal container filled with alcohol out of one hand and broke a glass ampule of morphine with the other hand. He went to the window to catch a ray of sun on his syringe and filled it. After he found a vein on grandpa's arm, I watched fascinated as some blood rushed back into the syringe. Slowly, he injected the fluid with everyone holding his breath. The crying of my mother and my two aunts filled the room together with the noisy, labored breathing of the patient. Everybody looked at the syringe as my father slowly injected the relieving drug. The labored breathing first became more intense. The rattling sounds gradually slowed and became less noisy. After ten minutes, grandpa took his last breath. In the following emotional let-down I was rushed out by my mother. I had just witnessed the ease of suffering which a medicine can provide. Later in my life I realized that I had encountered my first meeting with Euthanasia. This picture haunted me and appeared to me many times in similar situations during my life as a physician.

To give an idea of how stern and unforgiving Gustav Gerhardy was, the following story, whose details I found out during my last visit in Munich in 1992 when I met my older cousin for the first time. My grandparents oldest daughter, Ada, had become pregnant out of wedlock. This was an unforgivable sin particularly for the daughter of an officer of the Kaiser's Army. She had to leave the house. Nobody was allowed to mention even her name. My grandparents had spent a lot of money to further her singing talent for she wanted to be an opera singer. When grandfather found out about her dilemma, he gave her some money and expelled her from his home over the protests of his wife and crying three younger daughters. Communication with her was forbidden. She moved to Paris and lived with the father of her still unborn child. After the birth of her son they young couple lived under very primitive conditions since painters did not make much money in Paris. They never got married but had three more children. During the Thirties the whole family moved to Mallorca. The father tried to make a living by painting most of the churches on the island. Ada, who spoke four languages fluently, left her "husband" in Mallorca in the late thirties and moved with her four children to Paris where she found a good job. Later on she moved to Berlin and found an influential position and made enough money to escape her poverty and provide her children with a good education. Tragically, two of her sons were killed during World War II.

Dr. Medicine, Kurt Otto, Jürgen’s Father

Grandfather's domineering personality was governed by a strict honor code which was imprinted on his daughters and which filtered through to the present generation. It helped influence me during my learning years.

Kirchhofstraße 2 was fifty yards from a main street where streetcars rumbled by every day until midnight. Across from our street was a high brick eight-foot fence which surrounded the courtyard of a jail. The prisoners often filled the air with their loud singing through the open windows. They were just trying to kill time during their boring existences. Our apartment was on the first floor of the four-story house. Toward the street, blue flowered glycinias had grown all the way up to the second story. They gave some charm to the old apartment house, which was located in a lower middle class area.

As was customary a physician had 3-4 rooms adjoining his apartment, set aside for his practice. Thus day after day I could hear the patients walking to the first floor and filling up my father's waiting room. An appointment system was unknown. Ten to fifteen house calls were a normal load. Since patients had no transportation and also believed, that taking a sick person into the cold air was very dangerous, they called the doctor to their home

My mother was very ambitious for me. She thought I was mature enough to send me to school at age five. The first school day is still unforgettable in my memory.

Spandau as a western suburb of Berlin was full of industry with housing for lower middle-class and working people. The famous Siemens factory was close by and had its own town name: Siemensstadt. Ten thousands of factory workers lived around us. After the lost World War I, the Treaty of Versailles had caused serious depression and run-away inflation My father's mother as well as Uncle George and Aunt Frieda, his brother and sister, lived a half hour's train ride from the center of Berlin. A visit to them was always a pleasant change of pace. From this time I still have stamps given to me by my grandmother. They were ten Pfennig stamps overprinted with 100,000 Marks. This was just enough to mail one letter.

What a memorable day in my life it was, when my father bought an electric car! He was one of the first doctors in town to do so. Smaller than an MG, it was a One-Seater. The long hood contained twelve heavy lead batteries. The car was just fast enough to pass the streetcar. It could run for about 25 miles, then one had to reload it. The landlord had agreed to build a special garage for this vehicle at the end of a long driveway. Squeezed between the legs of my father, I rode triumphantly on my first school day - the only time ever I had a ride to school. I must have boasted about the fact that my father was the owner of such a rare vehicle. At the end of the first school day I invited my classmates to take a look at this unique automobile. They did not mind following me almost a mile from the school to our apartment. I had promised them a demonstration. My father had parked the car in the middle of the driveway, but I had not noticed that my father had left the ignition key in place. First I explained to my audience first, how one operates the car. Than I threw the lever, located on the side of the car, forward, to show my classmates how one can start the engines. I forgot to look at the ignition key. To my great surprise the car took off on its own. My audience cheered jubilantly as the car moved toward the garage. The electric motor, driven by twelve batteries, gave the vehicle a quick acceleration. It entered the open garage and hit the garage wall head-on. Battery acid splashed all over the floor, and the car, just two months old, was a total loss. The crowd also witnessed the second phase of the demonstration , which consisted of a furious father coming out of the house to see what the cheering and the noise was all about. He assessed the situation and dragged me into the house, where I harvested the only cane castigation of my life. My mother tried in vain to explain how lucky we were, that either the spectators nor I was injured. Not until the next day did reason take over.

Dr. Kurt Otto in his Hanomag

My father did not want to make house calls with the bicycle again. He was used to the auto by now. So after scraping his savings together, he went out to buy another car. This tune it was a Hanomag[^1], a car with a one cylinder 4-phase engine. The vehicle this time had two seats. It was round in front and in the back. The engine, located in the back, made the sound of a Diesel motor with its four-phase engine. We called it "the rolling loaf of bread." Because the car had no starter the engine had to be started like a motorcycle. A lever between the two seats kick-started the motor, and "A six year old should not be able to start it," the dealer told my father. How wrong could my father be ?? ! He again let me ride along on his house-call tours, this time in the passenger seat. Sometimes he allowed me to go with him to the patient's homes and observe him. The respect and trust of his patients was unlimited and enhanced the admiration I carried for my father. While I was waiting in the car during his calls I started experimenting with the starter lever. My previous debacle had taught me to be careful and knowledgeable about the mechanics of an automobile. So it took only a few tries, before I had the car running. My father appeared from the house call. I expected a scolding, but his initial protests subsided when he noticed that I did the job well

When I was nine Years old he received a call to rush to an accident-case which happened in a factory not too far from our home. A high wall surrounding the plant gave access to it. Father had parked the Hanomag within that enclosure. After one hour of waiting, I became restless and started the car. He still did not show up. After stopping and starting the vehicle a few times, I finally moved into the driver's seat, threw the car into first gear and started driving within the courtyard. From the second floor window, where my father was attending the injured patient, bystanders reported to him, what was happening below in the courtyard. The Hanomag was moving around the yard without a visible driver. Father came running out the door frantically waving his hands, and I obediently drove toward him, stopped the car and moved over to the passenger seat. This tune the scolding was not very severe, and as he was not yet finished with his patient he again disappeared. After another half hour he finally appeared, walked straight to car, where I had already restarted the engine and sat down on the driver's side and drove off without a word of disapproval. Perhaps he was proud that I could manage a car.

As I approached the twelfth year my father summoned me one busy late afternoon and gave me the car key. Our garage was three blocks from our apartment. Dad did not like to waste tune getting out the car for the house-call rounds. One day he gave me the key. ''Son, you get the car and drive it in in front of our house. Take my hat so the policeman, standing on the intersection, will not recognize you." This became a daily job. One day he had to drive to a small village ten miles out of town to make a call. During the dark rainy night the right front wheel came off and rolled a quarter mile down the road to disappear into the dense woods. The car came to rest on its axle and my father had to walk the rest of the way to the patient's house. The next day my mother and I went with the bicycle and after an half hour search found the wheel. With extra nuts we reattached it to the undamaged axle.

When I was ten years old, General Hindenburg- almost eighty years old- was re-elected as president of Germany. My father took me that Sunday to the parade on the main thoroughfare of Berlin. We shouted as loudly as we could in tribute to his 1914 war record, when he saved East Prussia from the advancing Russian Army. The Russians had encircled one German Army Corps, which included my father. This battle at Tannenberg defeated the Russians decisively and prevented the Russian imprisonment of my father.

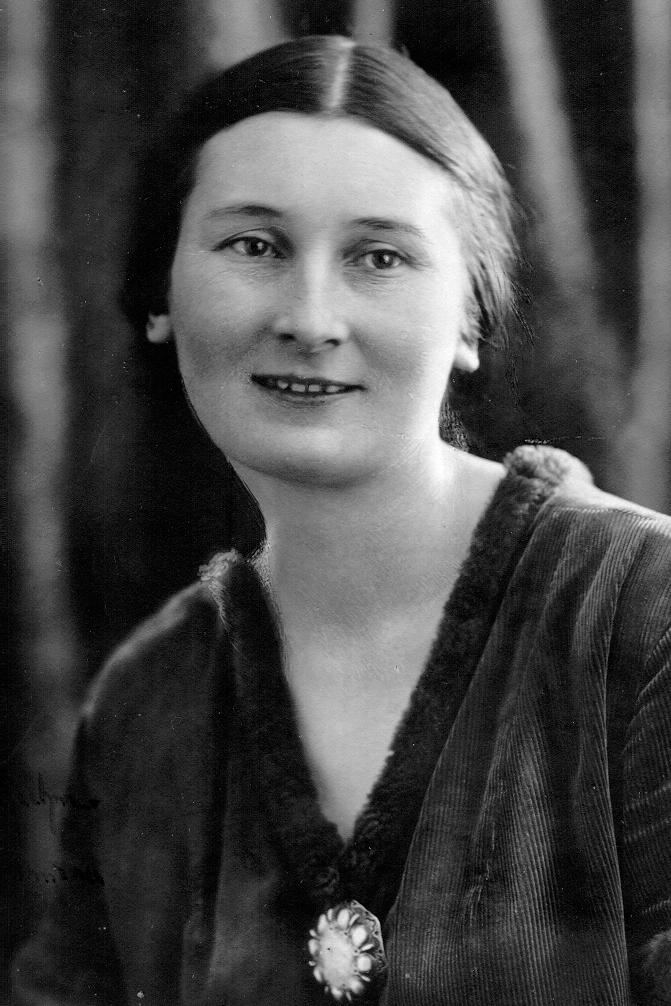

Ruth Otto, Jürgen’s Mother

After I had my fourteens birthday my mother called me one afternoon: "Dad wants to see you in his office."

I wondered what it could be. This was during his office hours'. Had I done anything wrong recently? My conscience was clear, so I hurried next door and knocked at his consultation room door.

"Come on in !" I opened the door with some trepidation. A middle-aged man was holding his arm, which showed quite a deformity. This must be a broken arm.

"Son, you have to help me pull this arm straight." Apparently, my father had injected some Novocain into the fracture area, since the patient seemed to be quite comfortable. The invention of Novocain in 1922 by my father-in-law had made it possible to give local anesthesia. My father wrapped a towel around the upper arm and told me to place myself firmly on the ground and hold on to the outstretched upper arm. Suddenly I felt a very strong pull. I could hardly prevent losing my foot-hold. With a dull snap the deformity straightened out.

"Help me put the cast on. Hold the arm tight and do not move."

My father took some wide bandages, sprinkled plaster of Paris from a box onto the bandage then immersed the bandage plus the plaster into a bucket of warm water and applied the cast. No X-rays were taken at that time. The feel of the bone and the look of the arm determined whether this was a successful reduction. From then on Father called me off and on either to show me some interesting findings or to help him. I had to empty a lot of kidney basins full of blood. He frequently removed a pint of blood from patients with high blood pressure. That lowered the blood pressure temporarily. Blood letting and Phenobarbital were the only remedies for this ailment. During the early thirties physicians had only a few means available to treat their patients with some grade of success. Many patients had to sit under an ultraviolet lamp to receive the "benefits" of its rays. There was an endless list of maladies which were treated this way.

Infected hand wounds and lacerations were almost a daily occurrence, and required office surgery at which I was allowed to help or clean up the mess.

In the early nineteen-thirties vitamins and their importance to humans was discovered. I had read some throw-away literature of my father's about them and mentioned it in our school class. That got me a job to give a talk to the class about these new discoveries. For two weeks I read every published article on the subject. My mother, who had studied six semesters of medicine before she joined the Red Cross in World-War I as an operating room nurse, made me some tables and drawings for demonstrations during the presentation. My scientific talk with its display was a great success.

One day during the flu season fifteen patients wanted the doctor for a home visit after 6 o'clock. Most families felt, it was appropriate to offer the doctor a glass of wine or a schnapps after he had taken care of the patient. That day my father had seen many patients with influenza in his swamped office and had skipped lunch. During the house calls he had received a number of these offerings, and on an empty stomach it must have affected his memory. When he came out of the home of the last patient around midnight he could not remember, where he had parked his Hanomag. He searched for a while in vain and finally called a taxi. Describing the location of his last house call, my mother took me along after midnight to find the car After half hour's search we finally saw it parked in a dark corner, eight blocks from our home.

I grew up with three siblings. My older sister Gisela was two years older than I. Her interests seemed always to be in a different world from me. Our parents did not have to give us very much guidance since we both were very independent and self-starters. We had good notes in school. Only occasionally my father entered my room at the six in the morning to asked for the essay I had worked one the day before and finished late at night although it was due for a whole month. He corrected then willingly the orthographic and grammatical mistakes. At that period Gisela was captivated by the contemporary poet Munchhausen. She bought all his poems and books, went to his readings and had his books autographed.

Jürgen’s Mother and her sister Hella

as

nurses in World War I

When Gisela finished her Abitur my parents thought she was to independent to live at home while she was attending the University of Berlin. So my mother decided to rent her a room for her in the Western part of Berlin and let her live an independent life. My younger sister Almuth was five years my junior. Her problems, if she had any, did not affect me. I felt that my mother would see after her well-being. Neither of us had any serious school problems. I don't think that any of us ever brought a bad grade home from school

My youngest brother Eckardt was the problem for all of us. Something must have gone wrong during my mother's pregnancy, hi retrospect I assume that during the delivery my mother must have had a period of lack of oxygen or had virus infections which had caused some brain damage to my brother, hi the first year of his life he was constantly sick. As tune went on my mother noticed that his I.Q. was always three to four years behind average and remained at the level of a ten year old My poor mother could never get rid of her guilt feelings She spent hours upon hours teaching him in order for him to continue his schooling. This often led to serious behavioral problems.

When my mother wanted to take him shopping and he wanted to stay home, Eckardt would throw himself on the street and scream that my mother was forcing him to go with her. One can imagine to what kind of embarrassment that led to in a town where everybody knew the doctor's wife. I witnessed many of these violent outbreaks of irrational behavior. My mother devoted eighty per-cent of her time trying to educate my younger brother. We other three children felt at tunes neglected. But thanks to the fact that we did not need much encouragement, we did not suffer from our mother's guilt complex.

At the age of eleven I discovered the effect of a convex glass which we called " Brennglass." It concentrated the sun rays on the glass to a temperature, which could ignite paper. One could bum all kinds of designs into any old newspaper. I wondered whether the "Brennglass" would also work, when one concentrated the sun rays through a store window. Such a window was available just next door, where a pharmacy had advertised the latest remedies. On a bright sunshiny afternoon I sat before the store window with my "Brennglass" and let the concentrated sun rays hit some decorative paper behind the store window. Not only did it smoke but a flame sprang up and took hold of the cardboard trimmings. Not hesitating a second I ran into the pharmacy and shouted: "You have a fire in the window." With a fire extinguisher and a big rag the pharmacist could take care of the situation just in time to prevent major damage. I wondered whether they ever figured out, how the fire had started.

Grandmother Gerhardy with One of Her

Grandchildren

It took me quite a while to persuade my father to let me take another trip to the pet store. This time I brought home a beautiful Chinese nightingale. She sang a lovely, melodious tune, which continued all day. After a month I found the door to the cage and the balcony door open with the nightingale singing her melody across the street in the trees. This ended my attraction to animals.

[^1]: der Hanomag© Irmgard & Jürgen Otto 1993 All

rights reserved

Zuletzt geändert: 06.06.2025 08:49:22